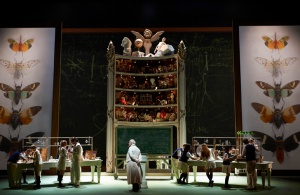

On October 26, 2013, a live broadcast from the Metropolitan Opera New York presented Shostakovich’s opera The Nose as staged in 2010, by William Kentridge. The story of The Nose is a predecessor to the theatre of absurd. The sense of humour of Eugene Ionesco or Monty Python is similar to that of The Nose. Being an accomplished artist Mr. Kentridge sensed the spirit of the story and created a set that combines the elements of Chaplin choreography, the shadow theatre, cartoon animation with a series of small scenes that rapidly follow one another in a dynamics akin to the one in the circus, by utilizing only the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the stage, as if deliberately dispensing with the dimension of depth, creating thereby the illusion of a film on stage. Mr. Kentridge decided to set The Nose in the time of Stalin’s Soviet Russia, the time when Shostakovich composed it. Well-researched documentary materials of prints, fonts and newspapers revives in a humorous way the spirit and aesthetics of soc-realism. Throughout the performance, a banner written in the English language that reads: “all will be revealed” was displayed repeatedly. It bears a curious aptness with a present-time exciting event, a matter to which we will return later.

On October 26, 2013, a live broadcast from the Metropolitan Opera New York presented Shostakovich’s opera The Nose as staged in 2010, by William Kentridge. The story of The Nose is a predecessor to the theatre of absurd. The sense of humour of Eugene Ionesco or Monty Python is similar to that of The Nose. Being an accomplished artist Mr. Kentridge sensed the spirit of the story and created a set that combines the elements of Chaplin choreography, the shadow theatre, cartoon animation with a series of small scenes that rapidly follow one another in a dynamics akin to the one in the circus, by utilizing only the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the stage, as if deliberately dispensing with the dimension of depth, creating thereby the illusion of a film on stage. Mr. Kentridge decided to set The Nose in the time of Stalin’s Soviet Russia, the time when Shostakovich composed it. Well-researched documentary materials of prints, fonts and newspapers revives in a humorous way the spirit and aesthetics of soc-realism. Throughout the performance, a banner written in the English language that reads: “all will be revealed” was displayed repeatedly. It bears a curious aptness with a present-time exciting event, a matter to which we will return later.

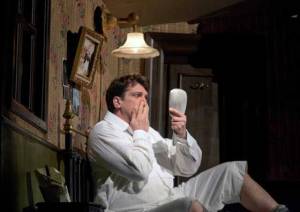

Paulo Szot, a Polish-Brazilian baritone and actor born in Sao Paolo, fitted the role of Kovalyov with confidence and charm, blending well among a majority of native Russian singers.

Paulo Szot, a Polish-Brazilian baritone and actor born in Sao Paolo, fitted the role of Kovalyov with confidence and charm, blending well among a majority of native Russian singers.

The story of The Nose, in short, goes like this: One day the barber Yakovlevich, minding his own business while peacefully having his usual breakfast, finds to his horror a human nose in his loaf of bread. The next morning Collegiate Assessor Kovalyev, a customer of Yakovlevich of the previous day, discovers to his horror that his nose has disappeared from his face. This bizarre opera is about the fugitive nose and the large-scale nosehunt to get hold of it and return it to its rightful place. At the end all is well and the nose is back where it belongs.

Nikolai Gogol wrote this satirical novel—some would say grotesque—in 1836. At that time, two czars, Alexander I and his successor Nikolai I, to be precise, ruled Russia. It was a time of censorship, surveillance and intellectual persecution of the greatest Russian poets Pushkin and Lermontov. From the broader historical time/event perspective, this novel was written 177 years ago in the era when humankind did not yet enjoy the benefits of electrical power. On the other side of the globe, the voices against slavery in the United States of America were met with violent opposition by pro-slavery mobs, and Charles Darwin was still sailing on his ship.

About a century later in 1928, Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his satirical opera The Nose, inspired by Gogol. It was at the time a few years after the death of Lenin, when Stalin was taking control of Russia. The recurring feature to Gogol time was that censorship, persecution and surveillance were taking firm roots in Soviet Russia, indisputably on a much larger scale. Shostakovich composed this opera as a satire on the times of Gogol’s life in Russia.

Fast forward another 85 years and we are watching a live broadcast of Shostakovich’s opera The Nose staged for the Metropolitan Opera in New York by William Kentridge, a South African artist living in Australia. He chose to set the opera in the time when Shostakovich was writing it, the time of Stalin’s Soviet Russia.

Surveillance and All WILL BE REVEALED appears as the recurring theme in the real life and art alike that makes Gogol’s nose protruding from of his overcoat in monarchy and dictatorship indiscriminately. Let’s examine what this is all about and can we relate it to our reality.

Nomen est omen. The nose, the organ of the sense of smell, alerts many species to danger or prey. It is the nose that gives us, humans, a precious, sometimes life-saving clue that something is wrong or suspicious. Or it can signal something unmistakably good. Figuratively speaking, the nose is the judge that gives a verdict on the sum of various little signs that stick out from the situation that we perceive through different senses, a visceral impression, a gut feeling that we process and declare: “I smell a rat”. The Nose metaphorically represents that instinct that leads us in a certain direction and gives us the first indication of something we urgently need to act upon. Nose is also a curiosity. The nose takes interest in the matters that concern us, but also those which are none of our business.

Satirical spirit of Gogol and Shostakovich is coincidentally awakened at the Met at the time of a blossoming surveillance of unprecedented magnitude. It is curious that in spite of its considerable age The Nose appears to be in sync with time. This phenomenon is also known. Its scientific name is synchronicity. C.G. Jung wrote an essay on that subject. We humans on this planet recently learned that surveillance is at its all-time peak. The secret we-know-whose-government’s nosy activity was upon revelation instantly high-browed and declared a matter of utmost national security. Means justify the ends and no one’s privacy is spared when the greatest nation of all has to confront its many, some yet unknown, yet potential enemies waiting only to blow their venomous and evil strike.

Diplomatic tensions tightened. Summits get cancelled. An American became a political refugee in Russia. Swiftly named as a traitor it was he who compromised the biggest Nose on Earth. Another misguided Nose whispered to a privy nose’s ear that the traitor was travelling to hide in Bolivia. The Bolivian President was almost under arrest in Vienna and his plane searched but the traitor was not there. France apologized. Austria silently shrugged and pretended not to be where the airport in Vienna was. The dispatched Seals were falsely alarmed and retreated quietly after their sudden emergence in this international imbroglio. The Nose’s contraband was handed to the Guardian. The harassment of the boyfriend at Heathrow was proclaimed a matter of foreign national security and as such presumably justified. A German Angela took offense at the practice of nosing her private cell phone and declared it conduct unbecoming among friends. All is compromised, and as it was shown in Kentridge’s The Nose– ALL WILL BE REVEALED. What a curious recurring theme!

The operetta which is being performed in headline news live, as you are reading this, is not a piece of art. We are only hearing a censored prelude. We do not quite know yet if it will end in shooting and singing, and who will laugh last.

Kentridge’s Nose at the Met is a fine piece of art, but the one more fitting for a museum. The Nose we still await to laugh at, is grotesquely real, growing, and still at large.